The Civil Society Monitor is a unique source of English-language information on the current state of Japan’s nonprofit sector. It seeks to link Japan’s nonprofit sector with the international community by reporting on current events and noteworthy activities and organizations in Japan’s emerging civil society.

The December 26, 2004, tsunami produced an immediate outpouring of support and sympathy from around the globe. The response of Japan’s civil society, though not as widely reported as the governmental and corporate response, was remarkable in terms of its scope, speed, and flexibility.

In the face of this tragedy, Japan’s governmental, private, and civil society sectors were among the world’s leaders in mobilizing resources. The Japanese government acted with unprecedented speed, committing $500 million for emergency assistance within a week. Corporations in Japan responded quickly by announcing both financial and in-kind donations, and according to the Japan Business Federation (Nippon Keidanren), corporate donations totaled more than $61 million as of February 22. In addition, a February 4 report by the Japan NGO Center for International Cooperation (JANIC) calculated that 31 Japanese NGOs had raised close to $60 million for relief efforts. By mid-March, that number had climbed above $100 million.

The response of Japan’s civil society sector highlights topics raised in other articles in this issue. On the one hand, the strength and speed of its response attest to the growing capacity of Japan’s NGOs to provide services to communities in need and its ability to complement governmental responses. In addition, new funding mechanisms, particularly those engaged in humanitarian relief, made possible a rapid response that would have been unthinkable a few years ago. On the other hand, the fragile financial environment for the nonprofit sector in Japan continues to hinder its ability to operate in emergency situations overseas.

Within days, Japanese NGOs had dispatched personnel to evaluate needs and capacities, rebuild shelters and sanitation facilities, provide emergency and preventive medical care, and distribute basic necessities. For example, the Japanese Red Cross Society dispatched one staff person to Sri Lanka and one to Indonesia within the first two days, and a 13-person health care team was sent to Indonesia on December 29, only three days after the tsunami. In the first two and a half weeks after the tragedy, the Japan Platform—a consortium of humanitarian relief organizations—allocated close to $3 million to six NGOs to dispatch teams to Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and India.

In the face of large-scale natural disasters, flexibility is often as important as speed, and many were surprised at the level of flexibility Japanese NGOs exhibited. In one case, Peace Winds Japan—which began its relief activities in Aceh by distributing emergency provisions—decided that, as basic needs were being met by other organizations, their resources would be put to better use by paying villagers to begin rebuilding their communities, providing much-needed labor and restoring the dignity of those people whose lives had been destroyed.

In Japan, as in many countries, large-scale and grassroots fundraising efforts mobilized extraordinary amounts of money from ordinary citizens. Online and personal appeals for funds in many cases exceeded targets, and music and sporting events were organized with all proceeds going to organizations directly involved in the relief effort. In addition, corporations such as Nomura Securities, NTT DoCoMo, and Panasonic introduced matching gift programs—a rarity for employers in Japan—as a complement to their other monetary and in-kind donations.

There has been some concern, though, that the outpouring of support from corporations and individuals for this incident may mean a reduction in private donations for other causes over the next year. Also, despite the speed and creativity demonstrated by Japanese NGOs in response to the tsunami, the inhospitable legal and financial environment continues to challenge their ability to respond to emergencies. Recently, there has been some progress at the national and local levels in developing funding mechanisms for select organizations engaged in humanitarian relief efforts. Still, many Japanese NGOs with a presence in the areas affected by the tsunami are not able to meet the complex criteria for receiving tax-deductible donations in Japan.

In February, the Coalition for Legislation to Support Citizens’ Organizations (C’s) proposed legislation to allow temporary tax deductibility for contributions for humanitarian relief activities over the next three years. If the legislation passes, Japanese NGOs working on tsunami relief will be able to raise crucial funds much more smoothly. In the longer term, passage of the bill could give Japanese NGOs greater access to funds, further expanding their role in international relief efforts.

In recent years, NGOs in Japan have increasingly focused on developing countries in Asia and around the world, coinciding with a similar expansion of governmental attention to Asia. While external relations had until recently been the exclusive domain of the central government, NGOs are beginning to change the way Japan interacts with the rest of the world. As their societal roles have grown, they have reached a critical stage in their development, and while they are becoming increasingly accepted in Japan, they still face significant challenges.

NGOs working on developing country issues first became active in Japan in the late 1970s with the influx of refugees from Indochina. New international development NGOs were established throughout the 1980s and 1990s, peaking in the mid-1990s. Since then, their roles have evolved, and the organizations themselves have become more embedded in Japanese society.

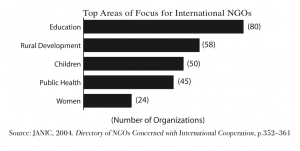

JANIC, an umbrella organization for international development NGOs, publishes a national directory, which in 2004 listed 226 organizations that meet its criteria as international exchange and development NGOs. These organizations engage in a wide range of activities related to 103 countries, spanning the fields of education, rural development, children, public health, and women. (See figure.)

While the emergence of this critical mass of organizations holds considerable promise, the environment for NGOs in Japan is far from hospitable, and international-oriented NGOs continue to face significant challenges.

While the emergence of this critical mass of organizations holds considerable promise, the environment for NGOs in Japan is far from hospitable, and international-oriented NGOs continue to face significant challenges.

Grassroots Interest

On the positive side, interest in international development NGO activities seems to be rising throughout Japan. In 2002, for example, as part of broader education reform, education for international understanding was introduced into the curriculum at some primary and secondary schools, creating opportunities for people from NGOs to come into classrooms and talk about their own experiences working with developing countries. Because this new course is being used to deepen the understanding that many young people have of NGO activities, it is producing a potential reservoir of new support for NGOs.

In recent years, Japanese university students, who have tended to be interested primarily in the United States and Western Europe, began displaying deeper interest in developing countries in Asia and elsewhere. University programs dealing with international development are being set up throughout the country, and their enrollment is reported to be roughly 35,000 students per year. As a result, there are more recent graduates seeking employment in international development, which is fueling the competition for jobs in NGOs and other relevant organizations.

More recently, local communities in Japan—which have also tended to focus on exchange with the United States and Western Europe—have become more interested in developing countries, particularly in Asia. People throughout Japan are increasingly exposed to international issues through contact with foreign students, workers, and visitors in their towns. At the same time, sister city relationships with Asian countries have grown, and there are now more than 300 with Chinese cities alone. These informal interactions, as well as an increase in travel around Asia, have helped deepen Japan’s understanding of its neighbors. In some instances, these interactions have inspired the formation of civic groups to help developing countries, and some have even grown into full-fledged NGOs.

Cross-Sectoral Partnership

The gradual acceptance of NGOs in Japan is also evidenced at the governmental level by the exploration of partnership between NGOs and the public sector. The Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) and the Japan Bank for International Cooperation have begun to encourage public participation in international cooperation activities and have sought to deepen linkages with NGOs. For example, the NGO-JICA Consultative Committee was established in 1998 to explore potential NGO input into JICA activities as well as to foster mutual learning. JICA and JANIC cosponsor training activities that aim to deepen understanding of the roles of NGOs as partners in implementing international development projects. One achievement of the committee has been the creation of joint training courses for JICA and NGO staff that enhance mutual understanding and explore potential collaboration.

Another important and innovative national-level partnership involves the Japan Platform, a new funding system established in 2000 to facilitate humanitarian relief delivery in response to natural disasters and refugee emergencies overseas. It is difficult for NGOs to anticipate when and where humanitarian assistance will be needed, particularly in cases of natural disasters. When disaster strikes, large amounts of money need to be mobilized immediately for travel, supplies, and security. However, the Japanese government tends to be slow in making funding decisions, and few Japanese NGOs have the financial resources to shoulder such expenses up front.

In response, the Japan Platform was organized to mobilize and coordinate humanitarian aid funding from the governmental and corporate sectors. It pools funds from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and corporate donors so that they are readily available when an emergency occurs. An advisory committee then distributes funds to 18 member NGOs, which provide humanitarian relief overseas. In the 2003 fiscal year, the Japanese government contributed ¥2.7 billion ($25 million) to the Japan Platform for assistance following the earthquake in Iran and for humanitarian activities in Iraq, and an additional ¥180 million ($1.6 million) was raised from corporations and individuals. Okayama Prefecture offers a unique and exciting example of a partnership between a prefectural government and humanitarian assistance NGOs. A mid-sized prefecture with a population of two million, it has proven that international-oriented NGO activity is growing not only in urban areas but also in smaller towns throughout the country. In April 2004, the prefectural government, encouraged by locally based humanitarian NGOs, passed a resolution to facilitate social contributions for international service.

One pillar of the new resolution was a decision to collect and store emergency supplies for use by Okayama NGOs when they respond to humanitarian emergencies overseas. The prefecture purchases some goods and collects others from towns, residents, and businesses throughout the prefecture. It then provides storage facilities for the supplies in a warehouse at the Okayama airport. The supplies are provided to NGOs quickly when they respond to an emergency. This system proved vital to the NGOs that provided humanitarian assistance to areas affected by the December 2004 tsunami.

Similarly, volunteers from Okayama Prefecture dispatched by the Japan Overseas Cooperation Volunteers (JOCV) program, which is operated by JICA and resembles the American Peace Corps Program, submit requests for specific items—such as medicine, educational materials, and other resources—to the prefectural government, which collects the items from Okayama residents and businesses and gives them to the JOCV volunteers.

Fundamental Challenges

Despite these promising new developments, Japan’s international-oriented NGOs still face several fundamental challenges. The term “NGO” is becoming more familiar in Japan as the number of organizations continues to grow and their activities expand in scope, but ignorance about what “NGO” actually signifies still prevails. According to an opinion poll conducted in 2001 by the Association for Promotion of International Cooperation, 64.7 percent of respondents did not know much about the activities of NGOs; 33.2 percent had a vague idea; and only 2.1 percent felt confident in their knowledge of NGO activities.

Why is the level of interest so low? One reason may be the lack of public relations efforts by NGOs. Another may be the underlying social tendency in Japan to regard government as solely responsible for looking after the public interest, hindering public acceptance of the legitimacy of NGOs. This points to a need for Japanese NGOs to focus on building public trust.

The danger that emerges in a climate in which Japanese nongovernmental involvement overseas is not entirely understood or appreciated was starkly illustrated by the domestic response to the April 2004 kidnapping of three Japanese citizens in Iraq. While none of the three were working for NGOs, they were engaged in nongovernmental work in a violent conflict zone. Upon their return to Japan, they were met with a wave of public criticism for ignoring government warnings and not assuming appropriate responsibility for their actions.

Another obstacle to further development is the lack of sufficient financial support for NGOs and the adverse effect this has on staff professionalization. In 2002, the total income for the 226 organizations listed in the JANIC directory was ¥26.67 billion (approximately $242 million), but close to half of the organizations brought in less than ¥20 million ($18,000). These smaller organizations are typically struggling just to survive.

In addition, most of Japan’s foundations and other funding mechanisms do not provide funds for capacity building. Without ample institutional funding, NGOs experience considerable difficulty attracting professional staff and have to rely on volunteers and part-time employees, preventing them from adopting more strategic approaches to organizational development. Currently, there are only about 1,000 full-time staff working for international-oriented NGOs in Japan. Of those, more than three quarters earn less than ¥4 million per year ($36,000), and about one quarter earn less than ¥1.5 million ($14,000) per year.

Finally, generational and experience gaps have given rise to differing perceptions within and between NGOs, making it difficult for the sector to develop clear directions and methods of operation. According to JCIE Chief Program Officer Toshihiro Menju, there is a significant generation gap between the people who established their own NGOs in the 1970s and 1980s and the younger generation of NGO staff. Many members of the senior generation did not start out with particular expertise in international development but based their work on their own firsthand experience working with local communities in developing countries. As a broad generalization, these NGO leaders are not necessarily interested in seeing their organizations expand or become more institutionalized, and this is often reflected in their organizations’ remuneration structures.

On the other hand, many NGOs have younger staff who have studied international development in universities or graduate schools. They place importance on increasing the organizational and financial capacity of NGOs and seek an appropriate salary for their professional work in the nonprofit sector.

In addition, according to Menju, there have recently been a growing number of cases of retirees engaging in NGO activities. For many, their priority is more on using their own skills and experience after retirement than on receiving an adequate salary.

The next few years will be critical for international-oriented NGOs in Japan. On the one hand, new opportunities for international interaction, increased understanding of the importance of NGOs, and innovative partnerships strengthen the likelihood that the sector will continue to grow at a rapid pace. On the other hand, if the institutional and societal challenges facing NGOs are not addressed in a comprehensive manner, their capacity for growth may be undermined.

Voyager Management, an American investment company, has recently begun contributing 1 percent of the profits from funds it manages to Japanese nonprofit organizations through a program operated by JCIE. The arrangement, referred to as the Social Entrepreneur Enhanced Development Capital Program (SEEDCap Japan), offers an innovative new model for nonprofit financing.

A mid-sized company that acts as a “fund of funds,” aggregating funds and investing them for small and mid-sized hedge funds, Voyager Management receives an incentive fee of 10 percent of the earnings on what it invests on behalf of several Japanese corporations. It then gives 10 percent of that amount—equivalent to 1 percent of investment gains—to JCIE for SEEDCap. JCIE, in turn, solicits applications for funding from Japanese nonprofit organizations, and a selection committee, which includes representatives from the Japanese investor companies, chooses the recipients.

SEEDCap was conceived by Ken Shibusawa, president of the investment advisory firm Shibusawa & Company and a descendant of Meiji-era business leader Ei’ichi Shibusawa, one of the founders of Japanese philanthropy. After graduating from an American university, he worked at JCIE, several U.S. investment banks, and a major hedge fund before becoming an independent consultant in Tokyo. Shibusawa was inspired to create SEEDCap “to be a bridge between two worlds—the financial world that is driven by economic returns and the world of highly motivated social activities.”

By addressing the interests of three sets of stakeholders, SEEDCap provides an alternative financing model for the civil society sector in Japan, where funding can be especially difficult to obtain. Investors take part because their investments yield solid financial returns, and, as an added benefit, they also realize a social return without bearing the direct cost of donations. Meanwhile, investment companies like Voyager Management are able to make social contributions with the confidence that their donations will be properly managed and distributed; at the same time they can better attract socially conscious investors. Finally, nonprofit organizations receive much-needed funding.

The first SEEDCap grant of several million yen has been awarded to OurPlanet-TV, an independent media portal established in October 2001 that operates as a nonprofit organization. OurPlanet-TV seeks to capture the stories of ordinary Japanese by presenting Internet broadcasts from their viewpoints on issues such as human rights and the environment. Viewers help produce the content of much of the programming, which consists of professional and amateur video and audio clips. By providing a forum for viewers to share their opinions, OurPlanet-TV hopes to encourage greater interaction with the media.

A second SEEDCap round is planned for 2005. Organizers eventually hope to increase the number of participating investors and to involve them more deeply in the program.

With public health experts increasingly pointing to the spread of AIDS as the gravest threat facing Asia, a new organization has been launched as a private support group for the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. The Friends of the Global Fund, Japan (FGFJ), which is chaired by former Prime Minister Yoshiro Mori and operates with JCIE as its secretariat, is working to encourage greater Japanese participation in the fight against communicable diseases. Since the spring of 2004, it has sought to heighten public understanding in Japan of the threats posed by these diseases, mobilize all sectors of society to participate in joint responses, and build cooperation between Japan and other countries in the regional and global struggle against these diseases.

UNAIDS is warning that Asia may soon surpass Africa as the region with the most HIV infections, and some analysts are projecting that the number of HIV cases in China alone is likely to reach the 10 million mark by 2010. However, in Japan, prevalence remains relatively low. An estimated 20,000 people have contracted the disease in Japan, and thus it comes as little surprise that societal awareness and media coverage are generally muted.

Still, the growing interconnectedness that is fueling the spread of HIV/AIDS in the region means that even countries with comparatively low prevalence rates are likely to face serious fallout from the epidemic. Regional security, social stability, and economic growth can all be affected as populations become debilitated, and experts insist that no country in the region can consider itself immune to the disease’s impact. For instance, economic integration between China and Japan has been growing rapidly, allowing China to overtake the United States as Japan’s largest trading partner in 2004. With all of the investment and trade linkages this entails, a widespread outbreak in China is bound to take a toll on the Japanese economy even if the infection rate in Japan remains low.

The Geneva-based Global Fund was founded in January 2002 at the urging of the United Nations, and it operates as a private foundation that mobilizes and then allocates governmental and nongovernmental contributions to fight AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria around the world. The Global Fund has been encouraging the establishment of private-sector support groups to help raise understanding of its activities in major donor countries, thereby promoting widespread involvement in the fight against communicable diseases. In addition to the FGFJ, a U.S. nonprofit organization called the Friends of the Global Fight was founded in 2004 in Washington, DC, with Jack Valenti as its president, and similar groups are being established in France and elsewhere.

The launch of the FGFJ was announced by former Prime Minister Mori at a March 2004 conference in Tokyo, and its advisory board—consisting of a diverse set of leading figures from business, government, labor, medicine, and the nonprofit sector—met for the first time in June. With initial financial backing from the Open Society Institute, the United Nations Foundation, and the Vodafone Group Foundation, the FGFJ promotes understanding of the Global Fund in Japan by disseminating information on the fund’s activities. This entails such activities as translating resource materials and, on occasion, it involves bringing Global Fund representatives and other experts together with leaders from various sectors of Japanese society for briefings and discussions.

In particular, the organization aims to raise awareness within Japan about the human security threat posed by communicable diseases and Japan’s international role in the response. It has begun outreach efforts to business, labor, and nonprofit leaders, and it has also been encouraging media coverage of HIV/AIDS. These efforts have included the formation of a multiparty task force of nearly 30 Diet members that meets regularly for briefings and discussions on issues related to the spread of AIDS and other communicable diseases. The FGFJ plans to lead a fact-finding delegation of task force members to severely affected countries in the region to explore how Japan can more effectively contribute to prevention, care, and treatment efforts overseas.

Another central goal of the FGFJ is to encourage cooperation between Japan and other East Asian countries in the regional and global fight against communicable diseases. It has launched a survey to assess business, civil society, and governmental responses to the spread of HIV/AIDS in countries around the region. Practitioners and scholars from 12 countries in the region are preparing studies on national-level policies to combat the epidemic. They will meet in Tokyo at a June conference to discuss their work, which will be compiled in a resource volume. Organizers hope that this study will lay the groundwork for a better-coordinated regional approach to the disease and contribute to the development of a network of regional leaders working to advance cooperative solutions.

More information about the Friends of the Global Fund, Japan, is available at http://jcie.or.jp/fgfj.

One of the most dramatic and least understood aspects of the post-World War II transition in the U.S.-Japan relationship was the process by which such bitter enemies became the closest of allies in a short period of time. While there have been many studies on the role of both countries’ governments in rebuilding the relationship, the important impact of nonstate actors—private philanthropy, academics, nongovernmental organizations, and other civil society actors—has been largely overlooked. In an attempt to develop a more complete picture of postwar U.S.-Japan relations, JCIE undertook a three-year research project on the “Role of Philanthropy in Postwar U.S.-Japan Relations, 1945-1975.” The findings of the study—which involved extensive archival research, in-depth interviews with some of the key philanthropic players in the postwar period, and a series of workshops in the United States and Japan—will be published in mid-2005.

While this project adds another important dimension to the study of U.S.-Japan relations by highlighting and analyzing the key role of philanthropy and civil society in the postwar period, it also offers some broader insight into strategies for reconciliation in post-violent conflict situations. In the case of postwar Japan, a small number of U.S. foundations encouraged reconciliation by building up the underpinnings of the relationship over the first three decades following the war. This study revealed that a core group of funders—the Asia Foundation, the Carnegie Corporation, the Ford Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, and John D. Rockefeller 3rd (JDR 3rd) and his various philanthropies—spent between $55 and $60 million on more than 4,000 grants related to Japan in the fields of international exchange, education, intellectual exchange, and civil society development. According to the study, private U.S. foundation objectives in Japan during the three decades following the end of the war reflected the contemporary intellectual trends of internationalism, New Deal progressivism, and Cold War liberalism. The individuals who led Japan-related funding were idealists with strong beliefs in the creation and sharing of knowledge, and they emphasized the development of intellectual networks and exchange.

Foundation objectives often coincided with—but were not driven by—U.S. government agendas of the time. Broadly speaking, they were committed to preventing a recurrence of war, encouraging democratization, stemming the spread of communism, and bringing Japan into the regional and international community. In order to satisfy those objectives, U.S. foundations sought to create programs for mutual understanding, develop the human resources vital to a strong relationship, establish an intellectual dialogue between the two countries, and build lasting institutions for exchange.

With objectives similar to those of the government, one may question the importance of private philanthropic initiatives to the bilateral relationship and to reconciliation efforts more broadly. Many of the foundation staff who were funding projects related to Japan have argued that they often found nongovernmental organizations better placed and better able than the government to support reconciliation. As one Ford Foundation official stated in a 1962 memo, “a foundation can contribute in some areas even more effectively than the government to the restoration of what Ambassador Reischauer has called the ‘broken dialogue.'”

Private foundations were able to operate from a long-term perspective and take more risks—within limits—on new institutions and controversial ideas. They deliberately reached out to Left-leaning scholars and other leaders in Japan, with the hope that they could engage them in a broader dialogue.

The lessons from this study highlight the need to focus on nongovernmental as well as governmental contributions in reconciliation processes following violent conflicts today. Governmental contributions after violent conflict often focus more on reconstruction of physical infrastructure than on the underpinnings of reconciliation. Private foundations and other nongovernmental organizations are more likely to be recognized as genuinely promoting reconciliation rather than promoting a particular government agenda. In addition, the underpinnings of reconciliation require broad participation throughout both societies that are rebuilding a relationship, and this cannot be done without support for grassroots and intellectual exchange. Private support, unencumbered by perceptions of governmental control and aimed at building mutual understanding and partnership at all levels, is critical to the reconciliation process.

Most of the key foundations active in U.S.-Japan relations provided support for area studies programs—American studies in Japan and Japanese studies in the United States—in an attempt to create a cadre of scholars in both countries who understood the complex cultural, political, and social context of their former enemies. The foundations also sought to develop mutual understanding using vehicles outside of the universities, by creating and solidifying institutions for exchange among a broader range of actors. The Japan Society in New York and the International House of Japan are two examples of organizations that owe their existence to private support from sources in both countries.

In addition to this emphasis on building and strengthening academic and intellectual exchange institutions, most of the foundations providing Japan-related funding in the postwar period focused much of their support on individuals throughout Japanese society. The Asia Foundation in particular provided a large number of small grants to individuals for travel and study abroad, with the explicit belief that allowing people to experience Western lifestyles and culture firsthand was the most effective way to convince them of the value of Western ideology. There was an attempt to engage current and future elites as well as individuals working at the grassroots level in order to embed understanding of and engagement with the West at all levels. Again, it was the Asia Foundation that focused most on the grassroots level, partially reflecting its organizational character and partially reflecting the fact that it had a representative on the ground in Japan and was therefore better connected among grassroots leaders than were its colleagues in other foundations who depended on their contacts with more elite actors.

It is important to note that the major foundations involved in postwar reconciliation insisted on forming equal partnerships with organizations and individuals in Japan. They were determined to encourage local leadership and a sense of ownership of the programs they funded within Japan. The idea was that Japanese citizens were best qualified to decide what Japan needed. This idea remains crucial to post-violent conflict reconciliation, which is something that can only emerge from interaction among equals.

One prominent example of local leadership over philanthropic initiatives was support for International House, to which the Rockefeller Foundation provided funding—at the urging of JDR 3rd—with the condition that matching funds of ¥100 million be raised within Japan. While this was a formidable amount of money at the time, a core group of Japanese businessmen and political leaders took on the task and raised the full amount, gaining the cooperation of more than 3,000 individuals and 5,000 corporations in their effort.

This example also highlights the importance of relying on existing networks and engaging influential actors with relevant knowledge and expertise. Japanese citizens were not able to travel to the United States during or immediately after the war, but a number of key individuals had experience living, working, or studying there prior to the war. Their keen understanding of the United States enabled them to work closely and productively with American foundations.

Many of the American foundation officials who were active in Japan-related funding after the war also had close ties to Japan, some through foundation-funded study before the war and others through military and government experience during the war and the Occupation. They recommended policies on Japan that at times seemed counterintuitive to their colleagues with little or no Japan-related experience. These individuals were able to draw heavily on their own networks to determine needs, strategically identify grantees, and encourage broader participation in projects and programs funded by the American foundations.

The world today is very different from what it was in 1945. Advances in international travel and information technology have opened up opportunities for communication among people and education on societies around the world. Still, we are faced with many of the same challenges to truly understanding other cultures and rebuilding relationships after periods of violent conflict. As we search for mechanisms for building strong, lasting relationships around the world today, there is much to be learned from the postwar successes of philanthropic initiatives to strengthen the U.S.-Japan relationship.

JCIE’s study of the role of philanthropy in rebuilding postwar U.S.-Japan relations will culminate in mid-2005 with the publication of an edited volume. It will include chapters on the following topics:

- Overview

- The Role of Philanthropy in Rebuilding Postwar U.S.-Japan Relations, Tadashi Yamamoto

- Nonstate Actors in Postwar U.S.-Japan Relations

- The Role of Philanthropy and Civil Society in U.S. Foreign Relations, Akira Iriye

- Japan-U.S. Intellectual Exchange, Makoto Iokibe

- The Evolution of U.S. Foundation Involvement in Japan

- The Evolving Role of American Foundations in Japan, Kim Gould Ashizawa

- An Analysis of Grants to Japanese Institutions and Individuals, Jun Wada

- Case Studies of Philanthropic Support in Pivotal Fields

- Promoting the Study of the United States in Japan, James Gannon

- Foundation Support for Japanese Studies in the United States, Kim Gould Ashizawa

- Grassroots-Level International Exchange in Japan and the Impact of U.S. Philanthropy, Toshihiro Menju

- The Role of Japanese Philanthropy

- U.S.-Japan Business Networks and Prewar Philanthropy in Japan, Masato Kimura

- Japanese Philanthropy: Origins and Impact on U.S.-Japan Relations, Hideko Katsumata

On December 24, 2004, the Koizumi cabinet announced plans for its administrative reform program, which included official guidelines for reform of the public interest corporation system, an important component of Japan’s nonprofit sector. The ongoing reform process, which the past two issues of the Civil Society Monitor have followed, has disappointed many civil society experts, who are deeply concerned that the proposed reforms may actually be a setback for the sector.

Japanese nonprofit organizations fall into a number of categories, the two most prominent of which are “public interest corporations” (koeki hojin) and “NPOs” (“specified nonprofit corporations” or NPO hojin). Approximately 26,000 organizations are classified as public interest corporations, including most of the larger, more established nonprofit organizations and private foundations, a sizeable minority of which are loosely affiliated with a government agency. Once they complete a lengthy and onerous authorization process to become incorporated under the provisions of the 1898 Civil Code, they are automatically awarded tax exemption on not-for-profit income. NPOs, meanwhile, can be incorporated relatively easily in accordance with the 1998 NPO Law, which also allows them tax exemption. They tend to be smaller than public interest corporations, and more than 20,000 of them have been established in the past six years.

The government’s reform initiative was launched in mid-2002, and a private sector advisory council on public interest corporations was convened in two phases by the Minister of Administrative Reform. In November 2004, the advisory council issued its final report, which included a series of proposals to be incorporated into the cabinet decision. However, except for replacing an authorization system with a registration system, the advisory council report and the subsequent cabinet guidelines offer little in the way of concrete measures to promote nonprofit activities.

The one major reform proposed in the government plan eliminates the need for organizations to solicit permission for their establishment from “competent authorities.” Currently, authorization for incorporation is awarded solely at the discretion of the government agency with jurisdiction over the applicant’s field of activities. For example, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is responsible for organizations focusing on international affairs. The proposed new system will, instead, simply award incorporated status to any nonprofit organization that registers and then complies with general rules.

The fact that public interest corporations will no longer need authorization for incorporation may seem like a step forward. But under the proposed plan, once they register, they then will have to seek additional authorization to confirm that they serve the public interest and should thus be accorded preferential treatment in terms of taxation and other issues. A new council will be established to make these judgments, but the lack of clarity as to its composition and autonomy is raising considerable concern. The final advisory council report recommended the creation of a new, independent entity, but the government changed this to a council under the jurisdiction of a state minister in the prime minister’s office that would include private sector experts. This indicates that the bureaucracy would likely extend considerable influence over the council and its decision-making processes.

Another major complaint about this reform involves its failure to set out concrete guidelines for judging whether organizations serve the public interest. The question of who decides and on what basis still remains to be resolved. Also, there are serious questions about what will be done with government incentives for nonprofit activity, most notably, the taxation system. Important issues, including the taxation of income, have been left undecided.

The cabinet secretariat for administrative reform is drafting bills based on these proposals for submission to the Diet in 2006. Meanwhile, the Tax Commission, which advises the prime minister on tax policy, will begin debating the taxation of nonprofit organizations in April 2005 and is likely to propose new legislation in January 2006. The lack of clarity about the concrete measures that will be included in the proposed legislation has fed apprehension in the nonprofit sector and is certain to stir further outcry once the measures are made public. In the meantime, the nonprofit sector will be closely watching the evolution of these bills and will continue to search for ways to make the legal framework more hospitable.