The Civil Society Monitor is a unique source of English-language information on the current state of Japan’s nonprofit sector. It seeks to link Japan’s nonprofit sector with the international community by reporting on current events and noteworthy activities and organizations in Japan’s emerging civil society.

In 2004, 4.9 million people became newly infected with HIV and 3.1 million people worldwide died of AIDS, nearly 260,000 per month. The monthly death toll is roughly equivalent to the December 2004 tsunami disaster, but this “silent tsunami” is being repeated every month, year after year, far from the gaze of television cameras.

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) recently estimated that 12 million people in the Asia Pacific region could become newly infected with HIV over the next five years. More importantly, it estimated that half of those new infections could be prevented if countries throughout the region drastically enhanced their prevention measures. As people cross borders more frequently, and as regional interdependence continues to grow, the economic and social impact of HIV/AIDS will be felt more acutely throughout the region, even in Japan, where the fight against AIDS has not yet been given high priority.

Japan’s Domestic Situation

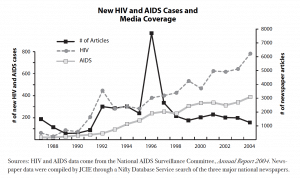

The first domestic outbreak of HIV in Japan struck hemophiliacs who were infected through contaminated blood products between 1982 and 1985 in what was eventually referred to as the “tainted blood scandal.” Today, studies estimate that there are approximately 20,000 people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) in Japan. Because prevalence is still very low, little public attention is given to the epidemic as a serious domestic threat.

Statistics reveal, however, that there has been a steady increase in the number of newly reported HIV infections and AIDS diagnoses in Japan, and experts warn that the epidemic may be spreading even more quickly than available figures indicate. Various underlying factors seem to be feeding this trend, the most predominant being changes in the sexual behavior of young people, greater migration across national borders, and delays in the early identification of infection due to the inadequate availability of testing and counseling.

The tainted blood scandal dominated reporting on AIDS for several years until a 1996 legal settlement was reached, acknowledging the negligence of the government and pharmaceutical companies. Since then, the general public’s awareness of HIV/AIDS has fallen dramatically, resulting in a low sense of urgency.

Today, approximately 100 community-based NGOs in Japan are involved in domestic HIV/AIDS-related activities—fewer than in the city of New York alone. They tend to be small-scale entities founded after 1990, with many led by doctors, medical staff, social workers, or PLWHA. Such organizations have come to play an important and growing role in prevention, care and support, and awareness raising.

As in other countries, NGOs in Japan are in a unique position to undertake HIV/AIDS-related activities that the government is not able to tackle. The recent spread of the epidemic is more concentrated among marginalized groups such as the gay community, drug users, sex workers, and migrant workers—groups with which government officials are hesitant to interact directly. NGOs, on the other hand, can interact with, and gain the trust of, a wider range of people. That direct access to the most at-risk populations makes it easier for them to create more appropriate and appealing prevention programs. For example, MASH (Men and Sexual Health) Osaka and Rainbow Ring are two notable organizations that have successfully implemented prevention programs with wide appeal among the gay population. In addition, at least one organization working with sex workers has made similar efforts.

The situation is similar for organizations implementing awareness-raising campaigns among the general public. The government pours money into large-scale prevention programs, but the young people at whom they are aimed often view the programs as overly moralistic. On the other hand, NGOs generally implement smaller programs that appear to resonate better with Japan’s youth. The Japan HIV Center, for example, trains young people to be trainers in AIDS education, and Positive Living and Community Empowerment, Tokyo, distributes a manual on sexual health geared toward young people. Some new organizations take a more direct approach by inviting Japanese youths to speak about prevention measures at events for their peers.

One of the most important developments among HIV/AIDS-related organizations over the last several years has been the creation of organizations by people who are HIV-positive. As in many other countries, the stigma of HIV infection is strong, and few people have publicly identified themselves as being infected with the virus. In 2003, however, a group of PLWHA created the Japanese Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS (JaNP+), a national organization that provides information on medical and social services, advocates for better living conditions for PLWHA and stronger protection of their rights, and creates linkages with other organizations in Japan and abroad. The creation of JaNP+ has blazed new paths for smaller organizations that have begun sprouting up around the country.

International Cooperation

On the international front, there are no Japanese NGOs that specialize primarily in AIDS-related issues. However, because many NGOs are working on reproductive health, primary health care, and other health issues—particularly in Asia—their expertise and activities in those fields have led to the inclusion of HIV/AIDS as one pillar of their work. Some small Japanese NGOs operating in Africa have taken up AIDS issues as one aspect of their community development programs. Overall, however, there are fewer than 20 Japanese NGOs involved, even tangentially, in HIV/AIDS-related activities in developing countries.

Meanwhile, one of the most noteworthy trends among HIV/AIDS-related NGOs in Japan is their growing efforts to build networks with counterpart organizations in Asia. The Seventh International Congress on AIDS in Asia and the Pacific (ICAAP), held in Kobe, Japan, in July 2005, appears to have added momentum to this movement, strengthening working relations between Japanese NGOs and their Asian counterparts.

ICAAP, which was established 15 years ago as an academic conference, has evolved into a forum for discussing policy in the fight against AIDS. With more than 3,000 participants from academia, civil society organizations, and PLWHA communities from around the world, the conference offered the opportunity for an inclusive discussion on regional approaches to AIDS. ICAAP’s vice secretary-general, Masayoshi Tarui, who is also vice chair of the Japan AIDS and Society Association, argues that “organizing the conference has had a major impact on Japanese civil society organizations working on AIDS. By strengthening their working relationship with other Asian NGOs and with international organizations, they have been able to place their own work in a broader international context. This will affect the future work of every individual NGO involved.” Tarui adds that “the experience of working together toward a common goal will hopefully encourage Japanese NGOs—which have taken a more scattered approach to the fight against AIDS—to combine their efforts for a more effective outcome.”

Government-NGO Relations

As the civil society sector in Japan has grown, the ability of NGOs to reach vulnerable population groups has paved the way for improved coordination between the government and NGOs. Gradually, though somewhat belatedly, NGOs in various fields have become involved in the policymaking process and in developing pilot programs in collaboration with the government. One such example is the creation of outreach centers for gay communities in Osaka and Tokyo, funded by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare. NGO effectiveness in reaching out to gay communities convinced the ministry of the importance of supporting such efforts and led it to create and fund outreach centers operated by NGOs. Prior to the establishment of these centers, the ministry’s funding to NGOs for HIV/AIDS-related projects was limited strictly to research, but these outreach centers have opened up new opportunities for the government to support NGOs in providing information on HIV/AIDS and health issues to one of the most vulnerable population groups in Japan.

Since 1994, NGOs have participated in regular meetings on health and population issues with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and these meetings have proven to be effective forums for promoting government-NGO collaboration. There are even several cases in Japan of NGOs receiving official development assistance for grassroots AIDS programs in developing countries. On the whole, however, there are still only a few examples of successful cooperation.

Toward a Regional Approach

Some Asian countries—such as Japan, Korea, Laos, and the Philippines—have low HIV prevalence rates, while in other countries—China, Indonesia, and Vietnam, for example—the epidemic is spreading at an alarming rate. Many of the factors that contribute to the spread of HIV infection—including trafficking in people and drugs, sex tourism, and migration—cross national borders, making rising rates in one country a threat to neighboring countries. In addition, Asian companies are becoming more and more dependent on markets and labor in other Asian countries so that the economic and human impact of the AIDS epidemic in one country increasingly affects the economic health of other countries in the region.

Recently, Japanese NGOs have begun undertaking a more regional approach to HIV/AIDS. Examples include the ICAAP conference in Kobe and a project undertaken by the Friends of the Global Fund, Japan (FGFJ)—administered by the Japan Center for International Exchange (JCIE)—that is bringing together 12 researchers from around the Asia Pacific to explore regional responses.

Still, it is becoming evident that Japanese NGOs need to be brought into this regional approach more thoroughly. While some NGOs in Japan are working on HIV/AIDS issues at the domestic level and some are active internationally, rarely are any of them involved with both. In addition, domestically oriented and internationally oriented NGOs tend to operate independently of one another, with little exchange of information and personnel. Just as the vertical divisions between government ministries in Japan are underscored by their tendency to develop independent policies, there is minimal coordination between domestic and international civil society organizations in their approach to fighting the epidemic.

>><<<

One of the complexities of HIV/AIDS is its potential to spread among marginalized groups of society in the earliest stages. Because the effects are not immediately visible, the infection often spreads widely and irreversibly before any preventive action is taken. Responses are often delayed because the issues involved—such as drug abuse, sexual orientation, prostitution, human trafficking, migrant workers, and sex education—are ones that spark divisive political debate and are consequently put on the back burner in many countries.

Some experts predict that, if the sense of complacency continues, the number of HIV infections in Japan could more than double over the next five years, reaching as many as 50,000 cases by 2010. That prediction, combined with the UNAIDS estimate of 12 million new cases in the Asia Pacific region during the same period, makes HIV/AIDS one of the most urgent challenges for the region. As the largest economy in Asia, Japan is faced with the task of bringing its domestic spread of HIV/AIDS under control while at the same time making a greater contribution to regional HIV/ AIDS countermeasures, not just in supporting individual country programs but also in implementing a more encompassing program for the whole region. Japan’s nonprofit sector is making strides in its efforts to meet this challenge, but the road ahead will be a long and arduous one.

This article is based largely on a paper by Satoko Itoh, chief program officer, JCIE, presented at a Tokyo symposium on the East Asian Regional Response to HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria, on June 30, 2005 (publication forthcoming)

Japan’s nonprofit sector has grown dramatically in the past decade, but NGOs remain plagued by significant financial woes. Like other Japanese NGOs, those involved in HIV/AIDS-related activities do not generally receive significant philanthropic support from foundations or corporations, nor can they depend on private donations or membership contributions, especially given the low level of interest in AIDS among the general public. As a result, few organizations have paid staff and many have to rely on volunteers, often medical professionals and PLWHA.

Part of the problem is the small size of Japan’s philanthropic sector. There are roughly 1,000 private grant-making foundations in Japan, and the combined assets of the entire sector stands at approximately $13.8 billion, comparable in size to the Ford Foundation, the third largest foundation in the United States. Most Japanese foundation grants are either research grants or scholarships; very few are made as project or program funding to support the type of activities pursued by NGOs. Even though these foundations operate more than 300 grant programs in the fields of health care and welfare—making this the second largest grant-making field after science and technology—few foundations have programs specifically focused on HIV/AIDS.

One such program is the Japan Stop AIDS Fund, which, since its 1993 establishment by the Japanese Foundation for AIDS Prevention, has made more than $1.8 million in grants. The fund collects donations from individuals and corporations and provides grants to NGOs engaged in social support activities and telephone counseling services for PLWHA. As the only grant program specifically targeting HIV/ AIDS, it has become an extremely valuable source of funding for NGOs in Japan. Unfortunately, however, donations to the Japan Stop AIDS Fund have decreased recently, reflecting poor economic conditions and a declining concern about HIV/AIDS.

Until recently, another example was the Levi Strauss Foundation Donor Advised Fund, administered by JCIE for seven years starting in 1997. The fund identified HIV/AIDS as one of its priority categories and provided a total of more than $300,000 in HIV/AIDS-related grants. The Levi Strauss fund was discontinued in 2004, however, further eroding funding for NGOs engaged in fighting HIV/AIDS.

On the corporate side, there is little incentive for corporations to pursue HIV/AIDS-related activities in a low-prevalence country like Japan. So far, none of the major Japanese corporations have become actively involved in the fight against HIV/AIDS. Their philanthropic programs tend instead to be confined to traditional social issues such as the arts, children and education, or care for the aged and the disabled. However, Japanese subsidiaries of some multinational corporations—including Levi Strauss Japan, the Body Shop Japan, MTV Japan, and SSL Health Care Japan—are involved in condom distribution, in-store campaigns, AIDS prevention messages, charitable giving to NGOs, and support for AIDS-related events.

Wider recognition of the social and economic impact of AIDS throughout Japan may prompt foundations and corporations to lend their support to Japanese NGOs involved in the fight against HIV/AIDS. Until that time, however, the financial base for such organizations will remain weak.

Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi pledged to drastically increase Japanese government funding for the global fight against AIDS and other communicable diseases at a June 30 conference in Tokyo that brought together leaders from the nonprofit sector, government, and the business world.

Noting the need to strengthen cooperation in battling communicable diseases in Asia and around the world, Koizumi announced a multiyear commitment of $500 million in new funding for the Geneva-based Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (the Global Fund), which is leading international efforts to finance the fight against three of the world’s most devastating diseases. Japan contributed $86 million for 2004, and the new commitment more than doubles its annual support.

The conference was hosted by the Friends of the Global Fund, Japan (FGFJ), and cosponsored by the Global Fund and Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The FGFJ—a civil society initiative that is chaired by former Prime Minister Yoshiro Mori and administered by JCIE—was launched a year ago to bring together leading representatives from business, civil society, government, medicine, and politics to encourage greater Japanese participation in the fight against AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria. This conference capped a weeklong series of FGFJ events targeting various sectors of society and commemorated the Okinawa G8 Summit that was hosted five years earlier by then–Prime Minister Mori and which provided initial impetus for the creation of the Global Fund.

Prime Minister Koizumi’s landslide victory in Japan’s parliamentary elections in September is being widely attributed to his success in framing the election as a referendum on structural reform. While public attention has been focused almost solely on his pet issue of postal system privatization, another reform initiative has also been quietly underway to restructure the nonprofit sector by revising the legal framework for “public interest corporations,” one of the main categories of nonprofit organizations, and by changing the taxation system.

On June 17, 2005, the Tax Commission, which was appointed by Koizumi following the December 2004 cabinet approval of the official guidelines for reform of the public interest corporation system, announced its proposal for a basic framework for taxing nonprofit corporations. Although the announcement is merely a proposal, it sheds light on the direction in which the commission is headed.

The highlight of the announcement, which many in the Japanese media jumped to cover, was the proposal that the tax system offer deductions on donations made to all nonprofit corporations that register under the new legislation and receive official authorization as organizations operating in the “public interest.” The announcement surprised many in the nonprofit sector, who have been deeply concerned that the ongoing initiatives will hurt rather than help the sector. If implemented, the proposed changes may provide significant incentive for corporations and individuals to make donations, potentially strengthening the weak financial infrastructure that is plaguing the nonprofit sector. Nonprofit professionals hope that the new tax system will encourage people to make cause-driven donations, a practice that is not yet common in Japan. Many remain worried, however, about how the proposal might be implemented and what its ultimate impact might be.

Another aspect of the proposed new tax system calls for nonprofit organizations to be taxed on income-generating activities. The question of what constitutes “income” is yet to be determined, but unlike the current tax system, which fully exempts public interest corporations from taxation, the new system may allow the government to tax some of their revenue.

The Tax Commission is expected to officially propose new legislation in January 2006.